All images courtesy of Jean-Baptiste Labrune on Flickr

Labrune began his experiments at the MIT Media Lab's Tangible Media Group, which focuses on 'facing the challenge of reconciling our dual citizenship in the physical and digital worlds.' Says Labrune (in a long, wonky interview with We Make Money Not Art): 'If we would make circuits on living entities, they would perform differently according to the environment or the homeostatic state of the substrate.' Translation: These orgatronics could rely on the natural processes taking place within the organic matter itself for power, or even interesting new functionality.

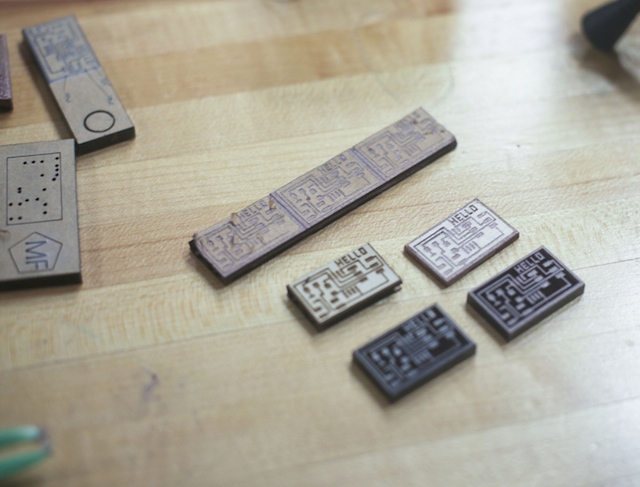

These laser-etched wooden 'chips' actually work.

Labrune's work has intriguing connections to the long-held dream of an 'internet of things': a world in which physical objects are all connected in a smart digital network, just like hypertext links or Google documents. The usual vision for such objects is some variation on RFID-networked kitchen appliances. But what if the 'smart things' were integrated more naturally -- like in a botanical garden, for instance?

Sure, no one wants to see ugly chunks of plastic hanging off of all the flowers in a park, but Labrune's orgatronics are just a first crude step toward better integrations of the digital and natural worlds. And besides, orgatronics don't even have to be permanent: 'A second [possibility] is the ability to create processes or machines that intervene into natural environment, but then withdraw themselves to let their artificiality being re-conquered by living entities, controlled by extra-human rules,' Labrune gnomically explains. Think of it like an Andy Goldsworthy project, but with wi-fi.

At the very least, it could be an intriguing solution to our e-waste problem.

[Read more at We Make Money Not Art]